The Fifteenth Amendment, granting black men the vote, was ratified on February 3, 1870. Black abolitionists, who had been struggling for decades against slavery and racial discrimination in the U.S. and abroad, saw it as one of their most consequential achievements. 2020 is the sesquicentennial of that constitutional landmark.

It is often asked when and where will the demands of the reformers of this and coming ages end? It is a fair question, and I will answer.

When all unjust and heavy burdens shall be removed from every man in the land. When all invidious and proscriptive distinctions shall be blotted out from our laws, whether they be constitutional, statute or municipal laws. When emancipation shall be followed by enfranchisement, and all men holding allegiance to the government shall enjoy every right of American citizenship.

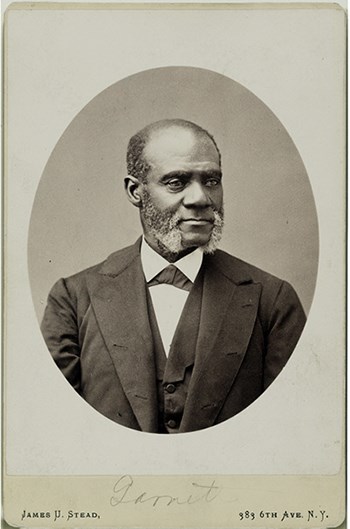

-Henry Highland Garnet, “Let the Monster Perish” (1865)

African Americans assumed prominent roles in the transatlantic struggle to abolish slavery between the 1820s and the Civil War. Some three hundred black abolitionists were regularly involved in the movement as speakers, writers, managers of anti-slavery offices, and in other very visible ways, while thousands more labored behind the scenes, including the work of the Underground Railroad. They heightened the credibility of the cause and broadened its agenda, shaping the struggle into America’s first civil rights movement.

Even as they fought for an end to bondage in the South, many black abolitionists lobbied state legislatures in the 1840s and 1850s for equal African American access to the ballot box. Racial spokesmen such as Frederick Douglass, Henry Highland Garnet, Amos G. Beman, Charles Lenox Remond, Martin R. Delany, and George T. Downing pushed for black suffrage or battled efforts for disfranchisement in states like New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Ohio, and Michigan.

When slavery ended in 1865, many white activists viewed their work as done and called to disband the American Anti-Slavery Society and similar abolitionist organizations. Black abolitionists, however, viewed slavery as part of a continuum of racial oppression – one component of a larger struggle. They protested that important work remained to be accomplished to make freedom real, including the achievement of full civil rights and the vote. Douglass argued that “slavery is not done until the black man has the ballot.” Garnet charged that “the battle has just begun in which the fate of the black race is to be decided.”

So, black abolitionists continued their fight for the vote. Many who had pressed for black suffrage before the Civil War redoubled their efforts as the nation moved into the Reconstruction years. When the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, abolitionists – black and white – hailed it as “a triumphant conclusion to four decades of agitation on behalf of the slave,” as historian Eric Foner observed in in his magisterial volume Reconstruction (1988).

This story is one of many to be discovered in the collections of the Black Abolitionist Archive at the University of Detroit Mercy.

Between 1976 and 1992, the Black Abolitionist Papers Project, supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, documented the work of the black abolitionists. This included an international search for sources that included thousands of letters, speeches, newspaper editorials, essays, sermons, and a variety of other materials. This collection was donated to the University of Detroit Mercy in 1998 and housed in a permanent archive.

The archive contains a wealth of materials that document the lives and work of the black abolitionists, including some 14,000 documents by the black abolitionists themselves; a sizeable microfilm collection of black and antislavery newspapers of the era; an extensive clippings file of contemporary biographical information on the black abolitionists; a library of scholarly books, articles, and dissertations on the black abolitionists; and other relevant sources. Roughly two thousand of these documents – mainly speeches and editorials – can be accessed online in a digital Black Abolitionist Archive.

The late historian James Horton called it “the most extensive primary source collection on antebellum black activism.”

Roy E. Finkenbine is Professor of History and Director of the Black Abolitionist Archive at the University of Detroit Mercy.

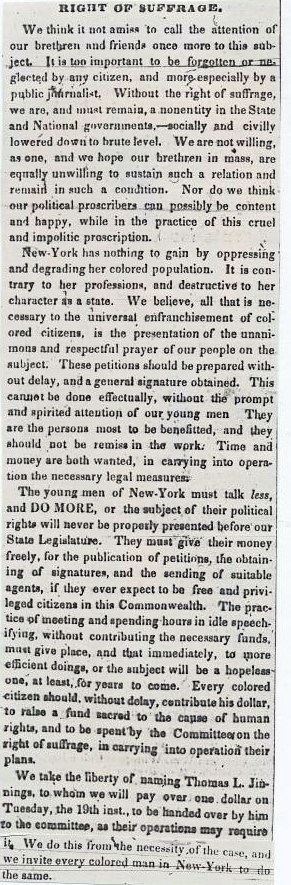

We think it not amiss to call the attention of our brethren and friends once more to this subject. It is too important to be forgotten or neglected by any citizen, and more especially by a public journalist. Without the right of suffrage, we are, and must remain, a nonentity in the State and National governments-socially and civilly lowered downtown brute level. We are not willing, as one, and we hope our brethren in mass are equally unwilling to sustain such a relation and remain such a condition. Nor do we think our political proscribers can possibly be content and happy, while in the practice of cruel and impolitic proscription.

New-York has nothing to gain by oppressing and degrading her colored population. It is not contrary to her professions, and destructive to her character as a state. We believe, all that is necessary to the universal enfranchisement of colored citizens, is the presentation of the unanimous and respectful prayer of our people on the subject. These petitions should be prepared without delay, and the general signature obtained. This cannot be done effectually, without the prompt and spirited attention of our young men. They are the persons most benefitted, and they should not remiss in the work. Time and money are both wanted, in carrying into operation the necessary legal measures.

The young men of New-York must talk less and DO MORE, or the subject of their political rights will never be properly presented before our State Legislature. They must give their money freely, for the publication of petitions, the obtaining of signatures, and the sending of suitable agents, if they ever expect to be free and privileged citizens in this Commonwealth. The practice of meeting and spending hours in idle speechifying, without contributing the necessary funds, must give place, and that immediately, to more efficient doings, or the subject will be a hopeless one, at least for years to cie. Every colored citizen should, without delay, contribute his dollar, to raise a fund of sacred to the cause of human rights, and to be spent by the Committee on the right of suffrage, in carrying into operation their plans.

We take the liberty of naming Thomas L. Jennings, to whom we will pay over on dollar on Tuesday, the 19 th inst., to be handed over by him to the committee, as their operation may require it. We do this from the necessity of the case, and we invite every colored man in New-York to do the same.